Today is National Corn Day in Guatemala, so we figured we could share some interesting facts about the most cultivated grain in the world, and one of the most cultivated crops.

Corn comes in different shapes and colors

As it is well known in most countries in Mesoamérica, there are corn varieties that produce different colors of grains (e.g. red, yellow, white, and black). However, varieties can also differ from one another for other characteristics. For example, from the more than 20 varieties that can be found in Guatemala (Orellana and Dardón, 2012) some are better suited for different altitudes and for different weather conditions. In this regard, it is common that the local varieties are categorized into varieties for warm, or cold weather; and as varieties for high, or low altitudes (Orellana and Dardón, 2012).

Moreover, recent studies continue finding new varieties. In fact, researchers recently found a variety that has been cultivated for centuries in southern México which has the ability to self fertilize. This variety produces a mucigel on its aerial roots where nitrogen fixing bacteria can live, creating a symbiotic relationship where these bacteria feed the plants nitrogen that they constantly fix from the air (BBC Earth Science, 2023).

Black corn cobs cultivated in San Martín Jilotepeque, 2014. Photo by Nicholas Hellmuth.

Where is corn cultivated in Guatemala?

According to Fuentes (2002), most of the corn that is cultivated in Guatemala is located beneath 1,400 masl, in what he names as the tropico bajo. More precisely, 68% of the corn cultivated area is in this region, which goes through the low areas of the departments of San Marcos, Quetzaltenango, Retalhuleu, Escuintla, Santa Rosa, Jutiapa, Alta Verapaz, Izabal, Huehuetenango, Quiché, and Petén.

The other 32% is located in the Altiplano (the volcanic chain region of Guatemala), above 1,500 masl.

Did you know that Petén is locally known by some people as the barn of Guatemala? 18% of the corn produced in Guatemala is cultivated here (Rodas et al. 2021).

Corn has a different way of doing photosynthesis

Corn plants belong to a small group of plants that includes around 3% of all plant species which are categorized as C4 plants. This designation refers to a genetic adaptation that has enabled these plants to reduce photorespiration, and thrive in regions with higher temperatures.

Such adaptation basically consists in the separation of the place within the plant tissues where two main important processes of photosynthesis occur. Photosynthesis generally occurs within the same cells in most plants. Nonetheless, C4 plants have different cells where different photosynthesis processes take place, enabling them to have the advantages mentioned before.

Maize field in Río Icbolay, Izabal. Izabal is one of the warmest regions of Guatemala. FLAAR photo archive, 2014.

Corn substitutes

It is a fact that corn has been cultivated as one of the main crops for millenia in Guatemala, leading back to Pre Columbian times. However, when corn was scarce, other plants were used.

For instance, the ramon tree (Brosimum alicastrum) holds a special place in history as it is believed that the ancient Maya people ate its nutritious seeds when there was not enough maize.

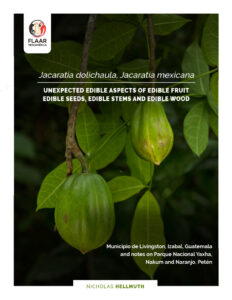

More unusual plants such as Jacaratia mexicana have also been used to make tortillas by some communities. If you want to learn more about this plant and how the Maya of Yucatán have used it check this FLAAR report:

In addition, it is important to note that local communities, particularly in Pre Columbian times, used to cultivate corn in association with other crops. So they got a varied supply of nutritious ingredients that they incorporated in their diet. Yet, the use of many of these crops has declined, particularly after the Spaniards colonized Mesoamérica.

Credits of the cover photo: different varieties of corn. FLAAR photo archive.

References

BBC EARTH SCIENCE

2023 This slime could change the world. YouTube, uploaded by BBC Earth Science. Apr.

9, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CFyd-kC6IUw

BEAR, R., RINTOUL, D., SNYDER, B., SMITH-Caldas, M., HERREN, C. and E. HORNE

2016 Principles of Biology. Open Access Textbooks. 1.

https://newprairiepress.org/textbooks/1

FUENTES, Mario

2002 El cultivo de maíz en Guatemala: una guía para su manejo agronómico.

Instituto de Ciencias y Tecnología Agrícolas [ICTA].

https://www.icta.gob.gt/publicaciones/Maiz/cultivoMaizManejoAgronomico.pdf

ORELLANA, A. and D. DARDÓN

2012 Aspectos generales y guía para el manejo agronómico del maíz en Guatemala.

Guatemala. Instituto de Ciencias y Tecnología Agrícolas [ICTA].

Available online:

https://www.icta.gob.gt/publicaciones/Maiz/Aspectos%20generales%20y%20guia%20para%20el%20manejo%20del%20maiz.pdf

RAMÍREZ-Sánchez, S., IBÁÑEZ-Vázquez, D., GUTIÉRREZ-Peña, M., ORTEGA-Fuentes, M., GARCÍA-Ponce, L. and A. LARQUÉ-Saavedra

- Breadnut (Brosimum alicastrum SWARTZ): an alternative for food security in

México. Agroproductividad. Vol. 10, No. 1. Pp. 80-83.

https://revista-agroproductividad.org/index.php/agroproductividad/article/download/943/802/

RODAS, A., MONTERROSO, I. and D. STOIAN

2021 Dinámicas productivas en torno al cambio de uso del suelo y sus repercusiones en

la Reserva de Biósfera Maya (RBM) en Petén, Guatemala. Working Paper 1. Centro para la Investigación Forestal Internacional (CIFOR), and Centro Internacional de Investigación Agroforestal (ICRAF).

Available online:

https://www.cifor-icraf.org/publications/pdf_files/WPapers/CIFOR-ICRAF-WP-1.pdf

Written by Sergio D’angelo Jerez